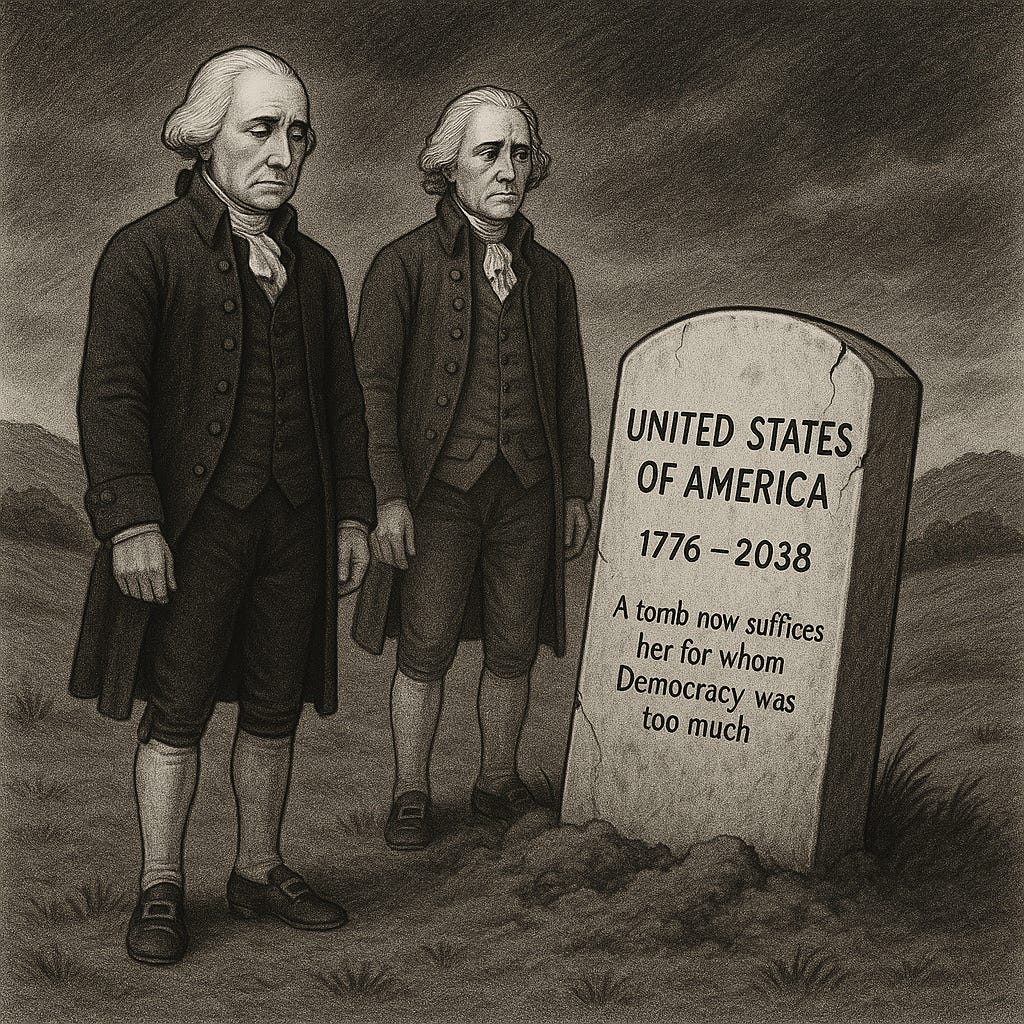

How It All Ends — Part III: The Breakaway

What Happens After the Center Fails

Recap: Parts I & II

In Part I, we followed the slow unraveling of the American federal system. There was no sudden break, only a gradual drift. Revenue declined, federal agencies weakened, and the Guard quietly shifted to local control. What kept the Union together wasn’t ideology or patriotism but institutional inertia. Once that disappeared, the flag still flew, but the center no longer held.

Part II discussed the decline of authority, deterrence, and legitimacy. Military units disintegrated. Control over strategic weapons became contested or weakened. Regional security councils formed, with some cooperating and others competing. International actors started to treat American successor blocs as sovereign states. What began as a drift has now split along strategic, political, and cultural lines.

Part III: The Breakaway

Section I: Dissolution

The Last President

No one knew when the President ceased being the President. There was no resignation, no final speech, and no ceremony. Press briefings went on for a while, growing more surreal as they took place behind blacked-out windows. Then they suddenly stopped, replaced by pre-recorded messages from staffers whose names later vanished from directories.

Rumors spread widely. Some said he escaped on a civilian Gulfstream from Andrews, headed to Zurich. Others claimed a foreign attaché took him to a secure estate outside Bogotá. The truth didn’t matter. The country had stopped listening long ago.

What remained of the executive branch vanished along with him. Cabinet secretaries issued statements that went unheard. Agencies shut their doors. The few still trying to “keep the lights on” discovered that no one was left to pay the bills. The Treasury itself had disappeared. Some attempted to rebrand as nonpartisan service bureaus or merge into state control; most simply locked up and walked away.

Congress Fails to Reconvene

Congress lingered longer before fading away. The Senate was the last institution to pretend it still had significance. When federal funding ceased, the Capitol complex went dark. Legislative sessions were shortened and often held in borrowed municipal chambers or back rooms of functioning statehouses. Without a quorum, they passed “resolutions of unity” for a republic that was already gone.

The House didn’t last very long either. Members from seceding states quietly took roles in provisional legislatures. Others disappeared into law practices, academia, or rural areas. A few tried to organize a new Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, but the only place they could find was an abandoned high school gym. Twelve delegates showed up. No one covered the event.

There was no final vote or act of dissolution. The Union gradually faded away, not with a bang, but as the last meeting place became too small, cold, and distant for anyone to care.

Washington D.C. Carries On

When the federal government ceased functioning, Washington, D.C.’s role as a national capital became outdated. The city itself still had neighborhoods, schools, and shops. However, its political core had stopped beating. In the initial weeks, regional leaders from Maryland and Virginia agreed to keep it alive, not as a seat of power, but as a shared civic hub.

Maryland took responsibility for Capitol Hill, the Mall, Georgetown, and the city’s northern neighborhoods, integrating them into its public safety and utility systems. Virginia expanded into South D.C., gaining control of the Navy Yard, Marine Barracks, Fort McNair, and nearby neighborhoods, which featured a mix of historic brick buildings, working docks, and new riverfront developments. Shared funding from both states quickly restored Metro service, with stations renamed for local landmarks. Although the city’s political center was gone, its neighborhoods continued to thrive.

Some tourists still visited the monuments, now cared for by state conservancies—museums reopened under university oversight, with their collections moving through Annapolis, Richmond, and beyond. The federal presence faded like a watermark in the sun. The District barely noticed, as many agencies had already abandoned their D.C. locations due to a lack of funding a decade earlier. It persisted, linked to two states instead of a broken-up Union.

What Survived Was Local Law

Without federal authority, most states relied on their existing laws. Criminal law mostly remained unchanged. Sheriffs still made arrests, judges issued sentences, and clerks stamped court documents — it was easier to stick with what was familiar than to acknowledge that higher authority was gone.

Some states, eager to legitimize themselves, quickly adopted former federal laws into their systems. Labor protections, environmental standards, and banking regulations transferred easily. Other states and blocs abolished anything related to the old order. Within months, the Southern Compact rewrote large parts of its civil code. It revised property rights, removed press protections, and trimmed tort law, which both critics and supporters called “Southern Sharia,” a process that had begun a generation earlier.

In some blocs, shared treaties began to hold legal power. Agreements on trade standards, energy grids, and mutual defense blurred the line between agreements and authority. The Pacific Compact considered establishing bloc-wide courts to resolve disputes; others relied on handshake deals, wary of anything resembling the old federal reach. Beyond these stable regions were the so-called “wild areas,” where civil authority was weak, and a ‘might makes right’ mentality prevailed.

Legal gray areas emerged around tribal lands, national forests, and former federal buildings, indicating upcoming sovereignty disputes.

Network Collapse

The Interstate Highway System, once the backbone of national travel and commerce, began to decline. States kept key lanes open where toll revenue or local security could sustain them. Still, without federal fuel taxes, coordinated maintenance, or national contracts, pavement cracked, bridges deteriorated, and some routes were closed entirely to prevent catastrophe.

The I-10 corridor was devastated. California maintained its section; Arizona kept Phoenix–Tucson open through private contractors and state patrols. From the New Mexico border to west of Houston, I-10 became a sun-bleached scar, broken by checkpoints and collapsed spans. Beyond Houston, the pavement improved into Louisiana, but the 90-year-old Calcasieu River Bridge finally gave way. Flooded bayou east of Lafayette finished the destruction, leaving the last stretches of I-10 as isolated elevated segments. Other major highways fared no better.

Passenger rail service collapsed in most regions. The Pacific Coast and Northeast corridors operated limited service. Freight lines split along regional lines, privatized in some areas and “nationalized” in others. Derailments were frequent, and locals salvaged tracks for steel.

Air travel splintered under regional aviation authorities. With the FAA gone, each state or coalition set its own safety rules. Screening procedures varied; some required biometrics, while others still accepted paper IDs. In many border regions, Canada and Mexico took over international airports and air traffic control: San Diego flights moved through Tijuana, El Paso through Ciudad Juárez, Detroit through Windsor. Their systems proved safer and eventually gained control of the cross-border airspace.

Domestic flights became similar to international travel. Pittsburgh to Denver might require a passport or a travel chit issued by the bloc and a layover in Omaha, as long and medium-range jet service had largely ended, replaced by aging turboprops with limited range.

The digital world fractured similarly. The old U.S. internet backbone persisted in patches, with frequent outages. Streaming services like Netflix operated from hubs in Dubai, Singapore, and Dublin, treating the former U.S. as just another market. Catalogs varied by region, and payments required foreign processors or prepaid cards. Television followed the same trend: local stations stayed on air, national news disappeared, and in border areas, Canadian and Mexican programming dominated. The BBC World Service and Al Jazeera became primary news sources.

The postal service shut down completely, replaced by regional co-ops, drone couriers, and blockchain-verified deliveries—only available to those who could afford them.

Section II: Rise and Rule of the Blocs

The fall of Washington didn’t end governance; it ended national authority. Power was spread out, and every ideology, tradition, and improvisation fought to regain control.

Some regions established governments based on shared values. Others governed through fear. A few attempted to maintain the Union’s structure. In the “Wild Areas,” governance completely broke down, similar to warlord-controlled Somalia in the 1990s.

The first two years after the Breakaway were not just chaotic, they were experimental. To outsiders, it appeared to be fragmentation; to those on the ground, it was about survival.

The Southern Compact: Unity Through Control

The Southern Compact was the first to take control, uniting Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and parts of Louisiana and Texas under a 'restored sovereignty' doctrine. Governance documents were drafted in secret and ratified without elections. Enforcement depended on National Guard units, former DHS mercenaries, and private security contractors.

Publicly, it pledged “Family, Faith, and Freedom.” Privately, it rewrote laws, imposed curfews, shut down independent media, and purged universities. Civic groups were dismantled or absorbed. Surveillance systems, some built on old federal infrastructure, others contracted from offshore firms, were reactivated. Dissent turned into sedition; sedition turned into terrorism.

Florida

Florida was the Compact’s eastern stronghold, but the Tampa–Orlando–Cocoa Beach line divided the state. North of it, the old South persisted. South of it, Broward, Miami-Dade, and Monroe resisted, connected to Caribbean trade and culture. The Keys became partly a republic and partly a smuggling hub.

The crackdown started with tariffs and inspections, then grew more intense. Compact units took over sheriffs' roles, radio channels were jammed, and mayors “invited” to Tallahassee rarely came back.

South of Palm Beach, distances and water shaped loyalties. Havana and Nassau were closer than Tallahassee. Trade with Cuba, the Bahamas, and Jamaica thrived. The Keys became a secure relay between Miami and the islands, protected by Cuban patrol boats and local militias. By the time the Compact tried to enforce a blockade, South Florida’s supply lines—and loyalties—were already Caribbean.

The Deep South

Georgia and South Carolina quickly moved to restore a moral hierarchy. Alabama and Mississippi, supported by militias and church-led governance, followed suit. Governance in this context became a spectacle: loyalty oaths in schools, parades, and book burnings. Control was inconsistent, mainly enforced where cameras were present.

The Energy Compact

Inside Compact territory, the Energy Crescent extended beyond it, including East Texas, Southern Louisiana, and Oklahoma, centered around Houston, Baton Rouge, Port Arthur, and the Permian Basin. It housed most refining capacity, LNG exports, and key ports.

These regions negotiated carve-outs: relaxed curfews, speech exemptions, and foreign trade privileges. In return, they facilitated the movement of oil and money. Houston resisted cultural dictates, and offshore platforms evolved into semi-autonomous nodes. The term “Energy Compact” began circulating quietly.

The carve-outs revealed hypocrisy: strict rules for the public, but none for boardrooms. In Texas, especially, wealth concealed deep divisions.

The Texas–Texas Problem

Texas was both a cornerstone and a contradiction. East Texas supported the Compact when business wasn’t at risk; South Texas opposed it, restoring bilingual education and cross-border trade with Mexico. Austin became an island of defiance. Houston tried to balance both sides until forced to choose.

The Intra-Texas War

The breaking point arrived when the Compact took control of border crossings. Local militias and defected Guard units, supported by Mexico, fought back. Counties switched sides overnight. By the Mexico-brokered ceasefire, Texas was divided: a Compact-controlled heartland and a Rio Grande coalition aligned with Mexico. The Lone Star myth was no more.

The Gadsden Question and Nuevo México

The collapse nullified the legal basis for the Gadsden Purchase, leaving its future uncertain. Southern Arizona and New Mexico became contested territory, neither side claiming it, and officials started informal discussions with Sonora and Chihuahua.

Within a year, power and supplies flowed north under joint agreements. Telecom, currency, and legal systems were integrated. By year three, Spanish became the default government language, and Mexican law governed most commerce. Without formal annexation, the Gadsden territories rejoined Mexico as Nuevo México, with El Paso del Norte (formerly El Paso) as the capital. Santa Fe dismissed it as theatrics, but a disputed UN plebiscite in year five confirmed the change. Mexico had regained land lost in 1854 without firing a shot.

The Pacific Compact: Progress Through Coalition and Technology

The Pacific Compact, comprising California, Oregon, Washington, and later Hawai‘i, established a parliamentary system with rotating executive leaders and a multiparty legislature. Transparency was key: livestreamed meetings, public budgets, and citizen councils. Technology handled transit, budgeting, and environmental monitoring under independent audits.

As climate migration grew, cooperation intensified. Los Angeles emerged as the unofficial capital, and the “New California Republic” nickname became tangible—a pact to survive together.

The New England Coalition: A Republic Remembered

Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut, and Rhode Island reinstated proportional representation and renewed local governance. Healthcare remained unified under a single-payer system. The I-495 tech corridor stayed profitable despite strict privacy laws. Boston and Portland coordinated ports to enhance food security, clean energy, and Canadian trade.

Mutual aid networks transformed into cooperatives, power syndicates, and medical mutuals. However, northern Maine and rural New Hampshire opposed integration, while Vermont grew closer to Quebec through shared infrastructure and climate policies. The coalition remained united through trust—minutes were published, audits shared, and aid was provided before requests.

The Great Lakes Compact: Practical Continuity

Illinois, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan kept the old republic’s structure but with limitations. Governors shared power with regional boards overseeing water, transit, and energy. Detroit coordinated industrial activities with Canada. Manufacturing resumed with green subsidies, and labor unions regained influence. Stability took precedence over reform.

Outliers and Ungoverned Spaces

New York City became a sovereign financial hub; Utah a religious republic; Alaska integrated with Canada; San Francisco, Seattle, and Boston turned into technocratic enclaves. Appalachia split into county rule, the Ozarks into militia fiefdoms, and the Mountain West into micro-republics—some holding nuclear stockpiles near former bases in New Mexico, Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas.

What Was Learned, and What Was Lost

Within two years, America had parliaments, dictatorships, communes, and surveillance states. Some prospered, others failed, and most managed through improvisation. The best systems were adaptable, included citizen voices, sustained services, and kept leaders accountable. Where power was hoarded or identities forced, rebellion arose.

Section III: The Return of Foreign Powers

What no one expected, and no civic charter mentioned, was the quiet return of the rest of the world. With Washington absent, foreign powers stepped in.

Mexico moved forward with trade and security agreements along the southern border, Canada strengthened its northern alliances, and China and Russia arrived with offers and influence. No flags were lowered, no embassies stormed, and no fleets approached.

It started with contracts. While blocs scrambled to control borders, others saw chances. America’s markets, military, and technology once defined the global order; now that center has disappeared, leaving a vacuum that calls out.

Oh Canada!

The northern border, long and porous, served as Canada’s opening. It reactivated dormant defense agreements, reviewed shared infrastructure, and coordinated with stable blocs.

British columbia established direct connections with the New California Republic. Vancouver became a center for digital governance, climate migration, and AI ethics. Canadian engineers assisted in repairing California’s northern water systems. Joint firefighting teams monitored what used to be the border.

In the East, Toronto and Montreal emerged as centers for American professionals. Trade with the New England Coalition restarted, and public health systems became connected. By year two, the Canadian dollar circulated in parts of Vermont and upstate New York.

Canada never claimed territory; it provided stability, and in return, gained influence over nearly a quarter of the former U.S.

Mexico Reclaims the South

Beyond the Gadsden Reversal, Mexico spread into the Southwest. Joint education programs expanded to Arizona, Mexican companies revamped utilities, and Spanish appeared on public signs.

Even blocs wary of annexation welcomed Mexico’s stability. Trade resumed, migration reversed, and medical supplies flowed. Cultural envoys reached New Orleans, Tucson, and Dallas; the Southern Compact signed customs deals despite its reluctance.

By the time Mexico obtained UN observer status for its affiliated territories, it was viewed not as a conqueror but as a steward—reclaiming strategic depth without firing a shot.

China Reasserts

China’s groundwork in fiber optics, telecoms, and port investments remained after the collapse.

In the Pacific Compact, Chinese AI companies offered to restore government systems in exchange for data access. Coastal cities agreed, and integration expanded. Oregon made a rare-earth deal through a Canadian front; Washington outsourced port security to a PLA-connected joint venture.

On the East Coast, some parts of the Southern Compact adopted Chinese surveillance tools, rebranded but still run by Chinese technicians. China didn’t need to occupy; it operated through infrastructure. America shifted from a market to a client.

The Russian Back Door

Russia sought access via Alaska, securing fishing and drilling rights, and through the Northern Prairie, where NGOs delivered supplies to isolated counties. Advisors, security consultants, and paramilitary-linked “liaisons” followed.

Kremlin-connected firms refurbished Cold War radar sites in Montana and the Dakotas. The Great Lakes Compact objected, fearing ICBM sites were also targeted for refurbishment, but without federal oversight, Russian hardware arrived freely. Moscow’s goal was disruption, and it succeeded.

Cuba: Medicine as Leverage

Cuba led with medical diplomacy—sending doctors, nurses, and vaccines. In some areas, they supplemented care; in struggling regions, they became the leading providers, earning trade concessions and quiet political alignment.

The EU Returns as a Bank

The EU recognized the Pacific Compact and New England Coalition as provisional states, thereby gaining port access, green energy contracts, and influence over AI governance.

Frankfurt banks loaned to the Great Lakes Compact, Nordic firms invested in Vermont and Michigan energy, and European fleets fished under licenses issued by Boston. Europe sought stability and policy sway, not territory.

The Gulf States and Others

The UAE built a logistics hub near Atlanta; Turkey patrolled the Southern Compact borders with drones. Israel partnered with ex-federal intelligence units on cybersecurity. India fostered education and research ties with the Pacific Compact.

Most deals were secret, and many were denied. In a world without a federal watchdog, everything was negotiable.

The New Diplomacy and Recognition

The UN Secretariat moved to Geneva. The U.S. seat remained physically in place but permanently empty, a precedent echoed by Taiwan in 1971 or Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

Recognition of blocs followed: Pacific Compact, New England Coalition, and, for containment, the Southern Compact. Less stable regions got aid instead. In McDowell County (formerly part of West Virginia), Pakistani blue helmets guarded World Food Programme teams.

By year three, the major blocs had flags, delegations, and intelligence networks. America was now a continent of embassies—native and foreign—competing for influence.

What Wasn’t Lost—Just Taken

Most citizens were too focused on survival to notice. No foreign flags flew, but protocols appeared in hospitals, engineers fixed power plants, and advisors met privately with governors and militia leaders.

America wasn’t invaded; it was offered deals it couldn’t refuse. The new empire came through fiber optics, grants, and armed couriers in plain clothes. Logistics replaced banners; security was promised, but at a price.

The age of self-determination had ended. The post-American era had begun.

Section IV: What Comes Next

There was no Restoration, no Second Union, no bold convention in Philadelphia. There was only the aftermath.

It was over. America did not vanish; it decayed first quietly, then unevenly, and finally everywhere. The house was torn down to its foundation. What followed was the forgetting that a house had ever stood there.

Everyday Life in the Former United States

For most people, the end of the Union was not the main trauma. The change was living without a country. Flags still flew in some places, more out of habit than loyalty. National holidays became local. Memorial Day in the Pacific Compact hardly resembled that in the Southern Compact. In Vermont, the Fourth of July was marked with candlelight vigils, while in Florida, it was celebrated with military parades led by contractors.

Identification varied. Depending on where you lived, you might carry a digital passport, a regional residence token, or a laminated card from your city council. In more lawless areas, proof of belonging was the weapon you carried. Tribal affiliations, both Native and newly created, re-emerged as a form of citizenship, complete with seals, councils, and enforcement. In many places, citizenship seemed to matter less each year.

Mail arrived irregularly. Gas prices were listed in multiple currencies. Children learned different constitutions. Schools taught various versions of the events leading to the collapse, and most eventually avoided the topic altogether.

New Maps, New Names

The U.S. seat at the United Nations was eventually removed from signage, seating charts, and official communications. In its place, a new brass plaque read “Puerto Rico.” The island was granted full membership after recognition by the Caribbean Compact and a majority vote in the General Assembly. For some, it was a compromise. For others, it served as a reminder that the United States’ last recognized voice belonged to an island it had once governed as a possession.

In the Security Council, the permanent membership dropped from five to four. No single bloc was seated in America’s place. Proposals to add a new permanent member stalled in rival claims from India, Brazil, and the European Union.

A few old names persisted, not out of loyalty but out of convenience. The dollar still circulated in parts of the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic, now with a pact-specific overprint. English remained the dominant language, though Spanish, French, and native languages such as the Navajo Nation’s Diné Bizaad re-emerged in school systems.

Even before the collapse, national identity was thin. People rarely called themselves simply “American.” They were Southern, Western, Irish, Hispanic, Appalachian, or something else. These identities had always existed, but they were once draped in a national veneer. Once that veneer was gone, those identities defined people entirely.

In contrast, France made “French” mean something despite centuries of regional rivalries. Italy united distinct peoples into a shared identity. America never did, and it paid for it with its demise.

The Digital Exiles

Some never accepted the collapse. They created virtual states, networks of memory, loyalty, and shared grievance.

Professional communities became unofficial digital embassies with their customs. Former federal workers formed encrypted collectives, sharing data caches and federal records now contraband in certain blocs. Digital archivists preserved Supreme Court decisions, congressional transcripts, and declassified memos as artifacts from a lost civilization.

Exiled journalists rebuilt fact-checking institutions on servers in Iceland, Taiwan, and in basement mesh networks in Michigan. Some communities lived entirely online. Members were born in one group, schooled in another, and employed across three, but their sense of home was a signal, not a place.

For some, the collapse ended a nation. For others, it began a diaspora.

The Ghost That Haunted the World

Abroad, the disappearance of the United States was not a cause for celebration. It was a wound with no clear treatment.

Pax Americana meant two things. At home, it was the idea of a country untouched by war since 1865, a myth built at the expense of Native populations. Abroad, it was stability enforced at others’ expense, often through airstrikes, coups, and economic coercion. The home version was comforting but false. The foreign version was closer to reality and began to unravel in the jungles of Vietnam and Cambodia in the sixties. When the American “peace” finally ended, the world did not find peace. It found ambiguity.

Some regions thrived in the space it left. China expanded cautiously. Europe stayed united. India asserted itself with a new purpose. Yet the ghost of America lingered in culture, weapons, and myths. No one filled the void, so the world adapted around it.

Others struggled. Russia risked losing its defining rival. In Pyongyang, artists painted over anti-American murals without knowing what to replace them with.

Nuclear weapons were among the most destabilizing legacies of America’s collapse. In Part II, the fate of atomic assets was left intentionally uncertain. ICBM fields on the Plains, ballistic missile submarines at Kings Bay, and strategic bombers at Barksdale remained stable at first. Over time, shifting politics left them in regions where maintenance faltered. Some warheads became tools of regional power. Others risked disaster from silo explosions, failed cooling systems, or floods. Foreign actors sometimes encouraged the instability, while others waited for time and neglect to take their toll.

The First Post-Americans

A generation was now growing up with no memory of the Union. “America” was a chapter in a history textbook, a cautionary tale, a symbol on their grandparents’ hats. They learned about it as earlier generations learned about Rome or Yugoslavia — with curiosity, but also with distance.

County fairs still displayed the Stars and Stripes as decoration. In VFW halls, a few surviving members kept the taps open, the beer cheap, and the conversation returning to Baghdad and Fallujah. In small-town churches and scout halls, the Pledge of Allegiance was recited as a ritual, not a declaration.

Most children pledged to something else, or nothing at all. They spoke not of reunification but of rebuilding, of starting something better, of avoiding the same mistakes. They sought stability, and they were learning how to build it from the ground up.

Native Nations

Native nations existed long before the Union, endured it, and with it gone, no one could stop them from rising. The collapse erased the Bureau of Indian Affairs and with it the mechanisms that kept the balance between manifest destiny and Native sovereignty.

Tribes responded quickly. Tribal police increased patrols. Gates appeared on roads crossing sovereign territory. Councils reopened negotiations on resource rights. Some allied with neighbors. Others stayed neutral but engaged with all sides.

The Legal Vacuum: Navajo and Mescalero Apache

With Washington gone, treaties lasted only as long as others honored them. The largest, the Navajo Nation, issued statements of reaffirmation and began new negotiations. It reinstated land protections, imposed local tax systems, and built partnerships with sympathetic counties and borderlands.

The Mescalero Apache of New Mexico faced disputes with new land barons over water and grazing rights. Santa Fe still claimed authority, but beyond the city, it was ignored. Some standoffs were peaceful. Others were violent.

The Boardroom Nations

Some tribes used capital instead of militias. In Connecticut, the Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan tribes bought distressed municipal assets in exchange for debt relief and public services.

Similar moves appeared nationwide. In Minnesota, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux secured major transport corridors. In Washington State, the Tulalip Tribes established joint governance with struggling cities. In Oklahoma, the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations emerged as economic anchors able to negotiate directly with blocs because of their oil reserves. In North Dakota, the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, known together as the Three Affiliated Tribes, became the only functioning authority around Minot. They assumed stewardship of the surrounding missile fields, inheriting a cluster of aging Minuteman silos that no other government could secure. For all of these tribes, liquidity and stability became sovereignty.

Epilogue: What Does Sovereignty Mean Now?

The surprise was not defiance but competence. Native healthcare and education systems had often outperformed surrounding states. Judicial systems functioned without interruption. Language preservation, land stewardship, and cultural continuity became models for resilience in a fractured continent.

They were not alone. Across the map, bloc governments—some democratic, others pragmatic, all shaped by necessity—proved they could keep lights on, water flowing, and streets safe. They struck trade deals, rebuilt infrastructure, and adapted laws to fit their people rather than a distant, vanished capital.

Together, Native nations and regional blocs became the backbone of what remained. From that beginning, something different could grow, not the old empire reborn but a patchwork of sovereignties learning, however uneasily, to share the same ground. In some blocs, cooperation replaced neglect. Territories once ruled from far capitals began to thrive under nearer, more accountable governments. Some regions were stronger, fairer, and more secure than they had been in generations.

Amid the silence of a fallen republic, the continent’s oldest governments still endured. In a land where many scrambled to build something new from the ruins, Native nations were among the few who had done it before, and never stopped. In the Caribbean, former colonies became regional powerhouses.

They knew collapse. They knew erasure. And they knew what most Americans had never been taught: survival is not the end of the story. It is only the beginning.

From that beginning, something different could grow, not the old empire reborn but a patchwork of sovereignties learning, however uneasily, to share the same ground. In some blocs, cooperation replaced neglect. Territories once ruled from far capitals began to thrive under nearer, more accountable governments. Some regions were stronger, fairer, and more secure than they had been in generations.

For those born after the collapse, and for many who came of age in its shadow, the United States would soon be only a subject in history books, not a living memory. They would inherit a continent of sovereignties, not states; of negotiated borders, not fixed ones. The lessons had been paid for over a generation of upheaval, and in centuries of struggle before it. What came next would decide whether the cost had finally bought something worth keeping.

Sources

Section I: Dissolution – Continuity of Government & Historical Precedent

Continuity of Government (Wikipedia)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continuity_of_government

Overview of U.S. continuity-of-government planning—designated survivor, emergency succession, relocation sites, and post-9/11 updates.

Federal Continuity Directive 1 (FCD-1)

https://www.gpo.gov/docs/default-source/accessibility-privacy-coop-files/January2017FCD1-2.pdf

DHS directive establishing continuity requirements: essential functions, orders of succession, alternate facilities, and communications protocols.

FEMA – Federal Continuity Planning Framework

Details Emergency Relocation Groups, devolution authority, and coordination steps if D.C. becomes unusable.

Federal Relocation Arc (Wikipedia)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Relocation_Arc

Describes the layered “A/B/C team” relocation network of federal facilities outside Washington, D.C.

Continuity of Congress (CRS Testimony)

Legislative contingency planning—special elections, quorum adjustments, and appointment authority.

Dissolution of the Soviet Union (Wikipedia)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dissolution_of_the_Soviet_Union

Precedent for superpower collapse without decisive battle: political fragmentation, economic crisis, and central authority dissolution.

Section II: Rise and Rule of the Blocs

Capita Economics – “What do we mean by geopolitical blocs?”

Defines “geopolitical blocs,” their characteristics, and modern re-emergence.

Cold War (Wikipedia)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cold_War

Historical context for bloc politics—Western vs. Eastern alignments, NATO/Warsaw Pact.

Cambridge University – “Back to Bloc Politics? From the Cold War to the New Type…”

The argument that 21st-century politics is returning to bloc-style alignments.

King’s College London – “The Return of Geopolitical Blocs”

https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/251955852/The_Return_of_Geopolitical_Blocs.pdf

Identifies contemporary blocs: less ideological, more pragmatic, including “swing states.”

Section III: The Return of Foreign Powers

E-International Relations – “The End of History and the Return to Geopolitics”

https://www.e-ir.info/2025/07/23/the-end-of-history-and-the-return-to-geopolitics/

This argues that global politics is shifting back to multipolar competition—China, Russia, and regional powers.

The Guardian – “A China-led global system…”

China’s effort to build a parallel world order through BRI, tech dominance, and diplomacy.

News.com.au – “‘Axis of Upheaval’: Nations form ‘alliance’”

China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea’s informal strategic alignment.

Air University – “The Return of Great Powers”

Reviews the resurgence of Russia and China as strategic competitors to the U.S.

Section IV: What Comes Next

Geopolitical Futures – “2025 Forecast: A World Without an Anchor”

https://geopoliticalfutures.com/2025-forecast-a-world-without-an-anchor/

Predicts instability from the lack of a single global stabilizing power.

World Economic Forum – “5 geopolitical questions for 2025”

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/11/5-geopolitical-questions-for-2025/

Abstract: Identifies uncertainties shaping global order in 2025.

Atlantic Council – “Welcome to 2035”

Explores plausible futures including war, tech disruption, and geopolitical shifts.

Atlantic Council – “Three worlds in 2035”

Envisions three possible world orders dominated by China, multipolarity, or fragmentation.

The Guardian – Gordon Brown on the demise of the ‘new world order’

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/apr/12/new-world-order-conflict-era-multilateralism

Commentary on the collapse of the post-1990 rules-based order and the risks ahead.

Author’s Note

This essay concludes a three-part series exploring how the United States might fracture, not through civil war, but through political, economic, and cultural erosion. From the first quiet shifts of Part I, to the decisive break of Part II, and now to the post-collapse world of Part III, the goal has never been prediction. Instead, I set out to build a plausible narrative from the patterns and pressures we can already see today.

I hope the series leaves readers with more than just a cautionary tale. The questions it raises — about governance, resilience, and identity — are ones we still have time to answer.